Antibodies have unique targeting specificity for different cell- and tissue-types. This has led to rapid growth in Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) for the treatment of cancer, which can deliver a cytotoxic payload to a particular cell-type or to cancerous cells that overexpress specific receptors. Oligonucleotides, such as antisense oligos (ASOs) and small-interfering RNA oligos (siRNAs), have the unique ability to silence specific genes or modulate their splicing or expression, however, due to their polyanionic nature, have difficulty being taken up by cells. By conjugating the oligonucleotides to antibodies, the resulting antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs) are readily internalized through receptor-mediated endocytosis. This greatly increases their potency, reduces adverse side effects and allows modulation of protein expression, including different isoforms of the targeted genes, in a tissue- or cell-specific manner.

Both AOCs and ADCs have three components: the monoclonal antibody (mAb), the linker and the payload (which, for ADCs, are small molecular weight drugs and for AOCs, typically an siRNA or ASO oligonucleotide). Of these three components, this article will focus on the linker which has large structural diversity and is a crucial component in designing AOCs and ADCs.

Linkers fall into two general categories – cleavable and non-cleavable. Of the 17 FDA approved ADCs, 13 have cleavable linkers [1]. At present, there are no FDA approved AOCs, however, for those in clinical studies, it’s a 50:50 split. All of Avidity Biosciences’ AOCs (4) that have been publicly disclosed use non-cleavable linkers and all of Dyne’s AOCs (4) use cleavable linkers.

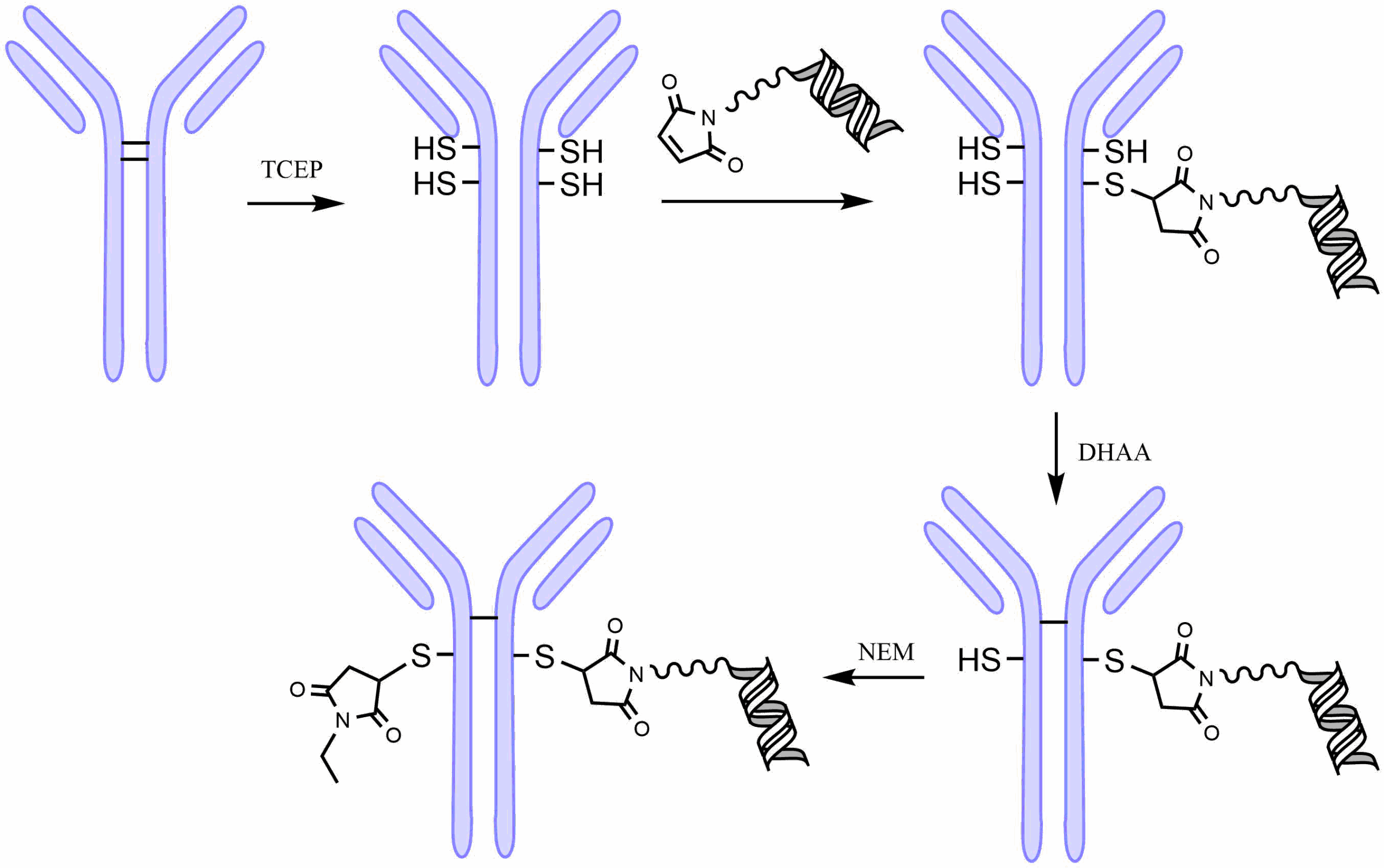

Both cleavable and non-cleavable linkers are typically attached to the mAb through a thioether linkage. All antibodies have multiple disulfide bond in the hinge region. This provides an easy way to label the antibody in a semi-selective manner (Fig. 1). First, the antibody is treated with TCEP to partially reduce the disulfide bonds between the cysteine residues. A maleimide-substituted linker-oligo conjugate is then allowed to react with the revealed thiols to make a thioether bond. Afterward, the disulfide linkages are reformed by oxidation of the free thiols with dehydroascorbic acid. The remaining free thiol of the cysteine opposite the maleimide-conjugated cysteine is capped using N-ethylmaleimide to prevent dimerization of the antibody conjugate over time.

Reprinted from: Structure−Activity Relationship of Antibody−Oligonucleotide Conjugates: Evaluating Bioconjugation Strategies for Antibody−siRNA Conjugates for Drug Development by Cochran, et al., J.Med.Chem. 2024, 67, 14852−14867 under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 public use license

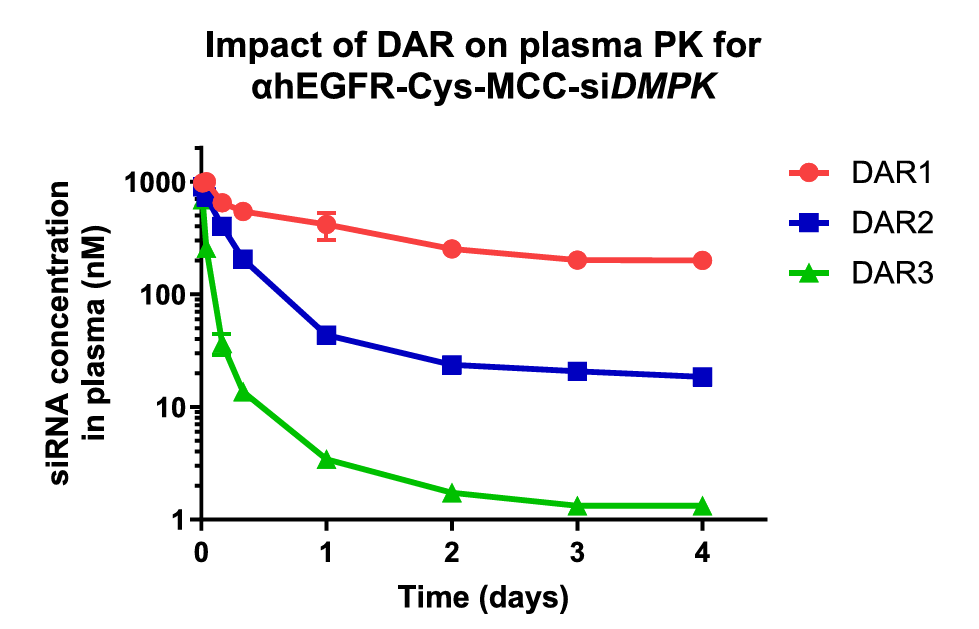

Unlike ADCs, the drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) should be limited to 1 for AOCs – at least in the case of siRNAs. An excellent paper by Cochran, et al., [2] investigated the structure-activity relationship of antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates. One of the many useful observations in the paper was that the rate of AOC clearance from blood serum was strongly dependent upon the DAR number as shown in Fig. 2. The serum concentration of an anti-EGRF mAb conjugated to 1, 2 or 3 siRNAs targeting DMPK is shown over time, clearly indicating a substantially higher rate of clearance with an increasing number of siRNAs conjugated to the mAb. By targeting thiols rather than lysines on the mAb surface, it is much easier to select for labeled mAbs with a DAR of 1.

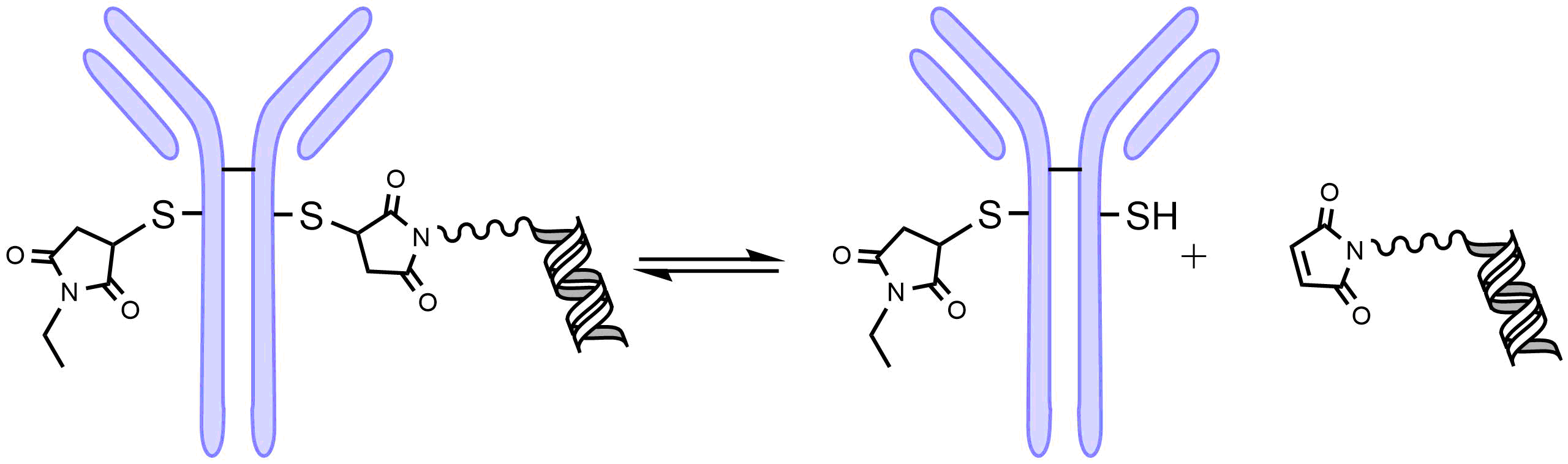

One drawback of the maleimide thioether bond is that it is reversible as shown in Fig. 3. This limits the stability of the AOC leading to lower activity and potential adverse reactions.

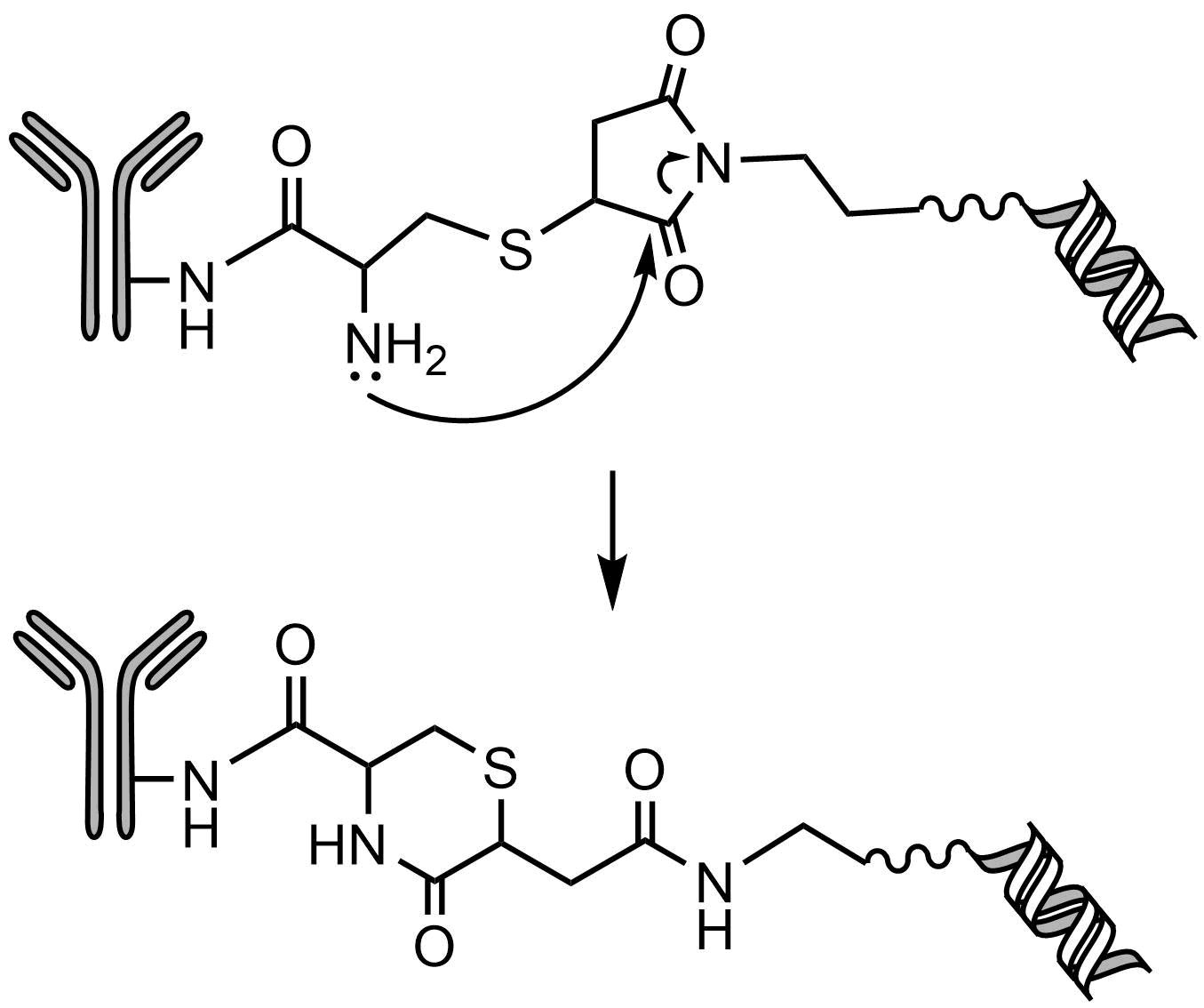

To avoid this issue, Lahnsteiner [3] was able to stabilize the thioether bond by placing a vicinal amine that led to the nucleophilic attack and hydrolysis of the thiol-maleimide conjugate, resulting a stable six-membered ring that eliminated the possibility of the retro-Michael conversion (Fig. 4). However, there are a number of options for conjugating AOCs to the mAb, such as the GlycoConnect™ technology that utilizes an engineered endoglycosidase in conjunction with a glycosyl transferase to insert an azido-modified GalNAc [4]. This provides a means for site-specific click reactions to attach strained cyclooctynes-labeled linkers. Further conjugation strategies are described in detail in the review of Lei et al. [1].

Non-Cleavable Linkers

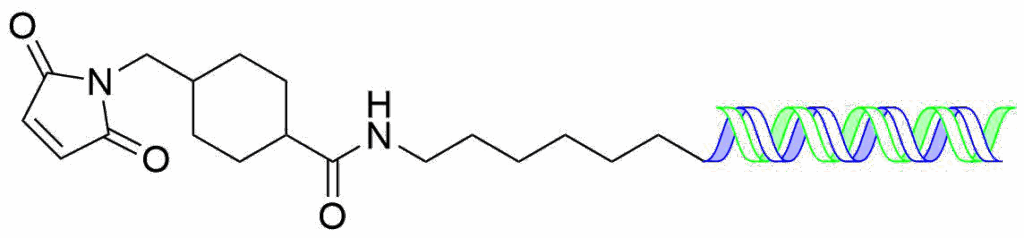

Non-cleavable linkers are not subject to cleavable by chemical or enzymatic means and are attached to the sense-strand of siRNAs where they cannot interfere with the loading into the RISC complex. They are extemely stable in serum which limits adverse side effects and slows clearance. Typically, they are heterobifuncational linkers with an NHS ester on one terminus and a maleimide on the other. The linker if first reacted with an amino-modified oligonucleotide under conditions to avoid hydrolysis of the maleimide and then reacted with a cysteine of the mAb. The simplest example of this is the SMCC linker (Succinimidyl-4-(N-maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate) shown as the oligo conjugate.

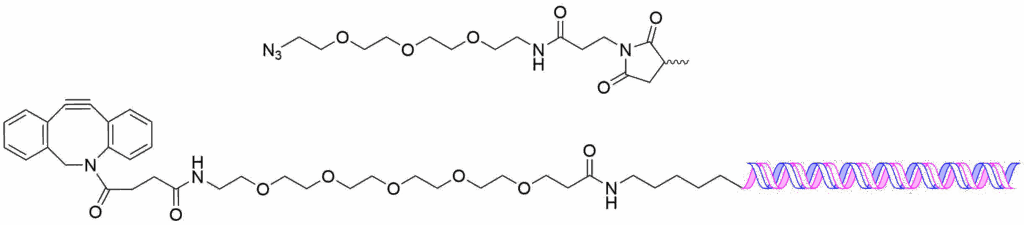

To present an example of a copper-free click conjugation, shown below is the DBCO-PEG5 linker conjugated to an amino-modified sense-strand of an siRNA and it’s corresponding azido-PEG3 maleimide which is coupled to the mAb.

Cleavable Linkers

Cleavable linkers are designed to release their oligonucleotide payload when the AOC has been pulled into the cell by receptor-mediated endocytosis. As the endosome matures, the pH is lowered and they acquire various proteases, nucleases, lipases eventually becoming a fully-matured lysosome, with a pH of 4.5-5.

The differences between the physiological conditions inside and outside the cell, allow linkers to be designed that can be triggered to cleave upon uptake into the cell. These include:

- Low pH. When going from serum into endosomes/late-endosomes and lysosomes, the pH drops from pH 7.4 to pH 5 or lower.

- Reductive potential. The concentration of glutathione, which reduces disulfide linkages, goes from low micromolar concentrations in extracellular serum to low millimolar concentrations inside the cell.

- Peptidase activity. Cathepsins (of which there are many) and legumain, are typically highly localized in late-endosomes and lysosomes. However, often in cancers they are upregulated can be excreted to the extracellular matrix.

Linkers that cleave in low-pH environments have acid-labile functional groups such as hydrazones, acetals, and carbonates. However, while the rate of hydrolysis at pH 7.4 is greatly reduced, it’s not eliminated. The first ADC that was approved Mylotarg® in 2000, used a hydrazone acid-labile linker, but was voluntarily withdrawn from the market due to its instability in plasma in 2010. However, it was reapproved in 2017 for refractory and relapsed CD-33 positive AML using a lower, fractionated dosing schedule.

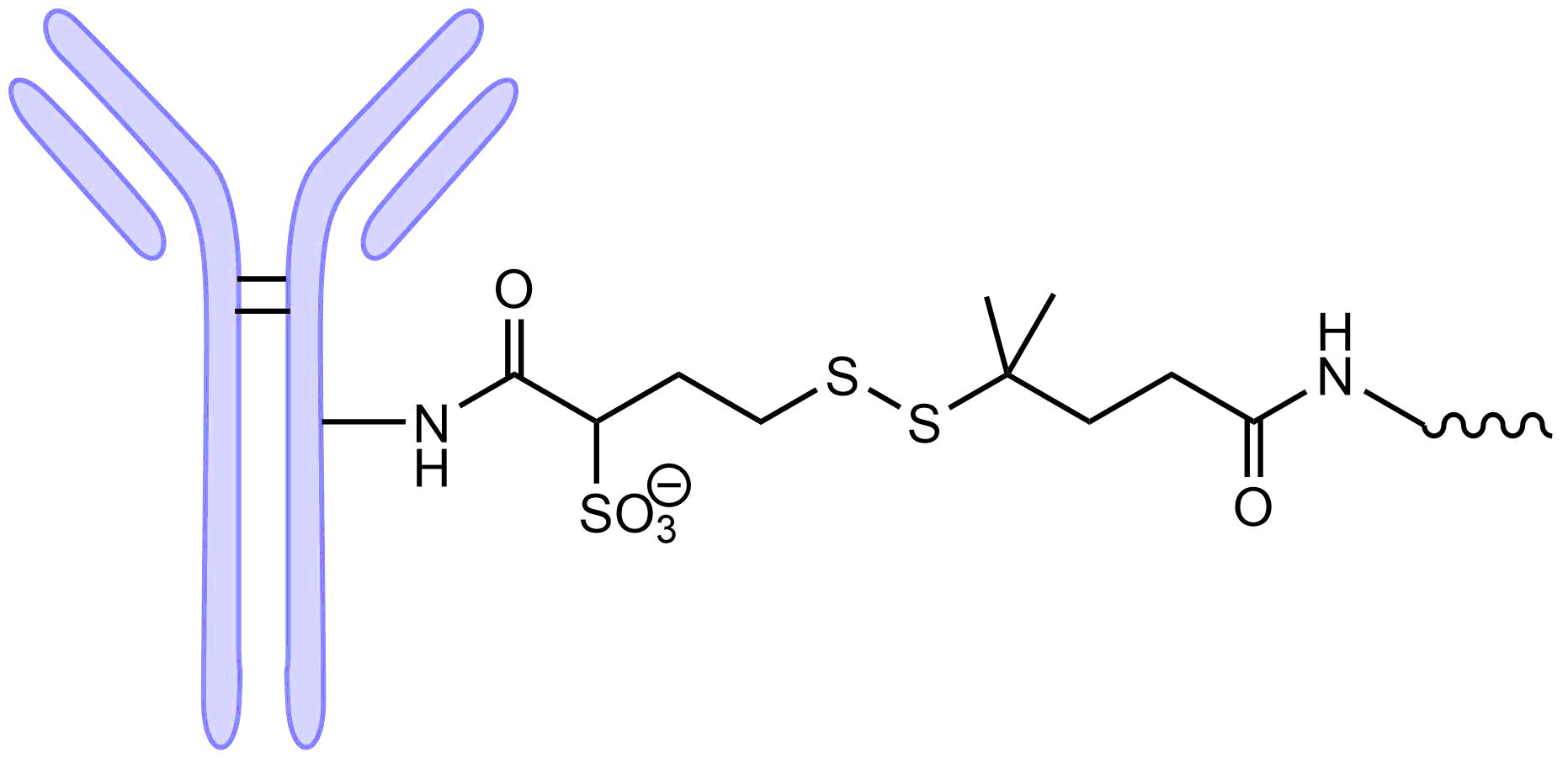

Stability is also an issue with reducible disulfide linkages. The stability can be improved by placing a geminal dimethyl group adjacent to the disulfide as was done for the anticancer ADC drug ELEHERE which was approved by the FDA in 2022. However, having a somewhat ‘leaky’ linker for small molecule anticancer drugs can be a benefit. It allows the ‘bystander’ effect to occur, where even though the mAb is bound to the surface of the tumor, the drug is released and can diffuse deep into the cancerous tissue. For AOCs, however, released siRNA would not be able to pass through the cell membrane due to its size and polyanionic nature and therefore any passive release is expected to just lessen its activity and potentially increase adverse side effects.

Enzymatic Triggered Cleavage

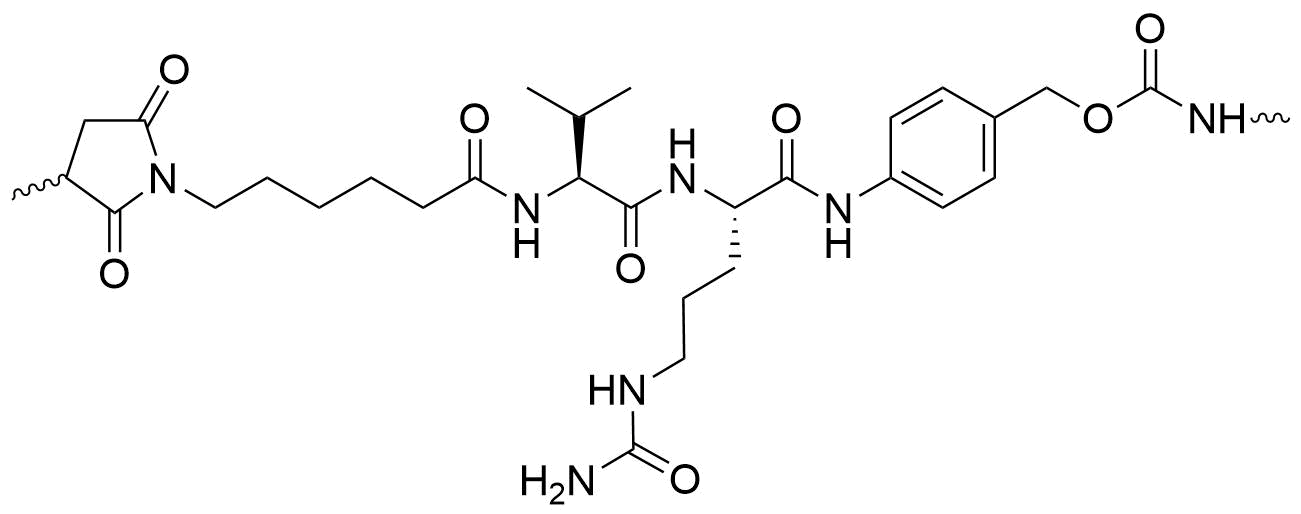

There are a number of peptidyl linkers that are cleaved in the late-endosomes and lysosomes that are remarkably stable in plasma. One of the most popular is the Valine-Citrulline linker (Val-Cit) shown here.

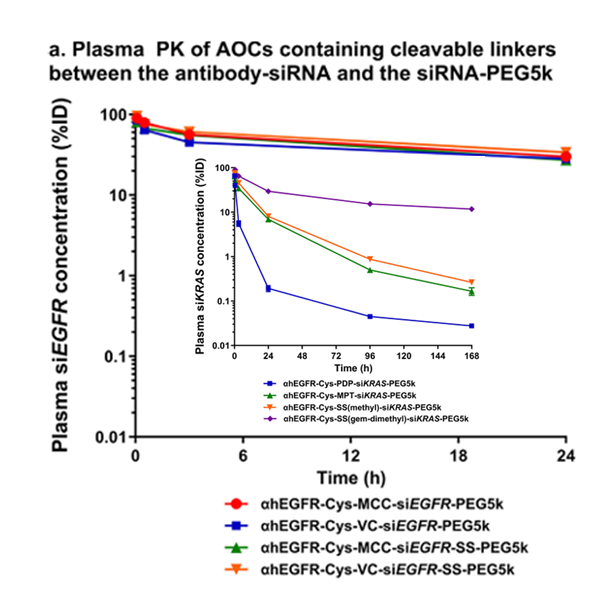

A comparison of the stability of the Val-Cit cleavable linker versus the non-cleavable SMCC linker is shown in Fig. 5, where the percent Injected Dose of AOCs is followed over time. The plot shows that stability of the cleavable and non-cleavable linkers to be virtually the same. Unfortunately, the results are slightly obfuscated by the presence of the 5kPEG, however as seen in the insert, the 5kPEG did not prevent cleavage of the various disulfide linkages. Note the vicinal gem-dimethyl disulfide was the most stable of the disulfides indicating the importance of steric hinderance to maintain disulfide integrity. The excellent stability of the Valine-Citrulline linker (Val-Cit) is perhaps one of the reasons that all of Dyne Therapeutics’ AOCs uses a cathepsin B cleavable linker (its exact structure has not been publicly disclosed).

Reprinted from: Structure−Activity Relationship of Antibody−Oligonucleotide Conjugates: Evaluating Bioconjugation Strategies for Antibody−siRNA Conjugates for Drug Development by Cochran, et al., J.Med.Chem. 2024, 67, 14852−14867 under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 public use license.

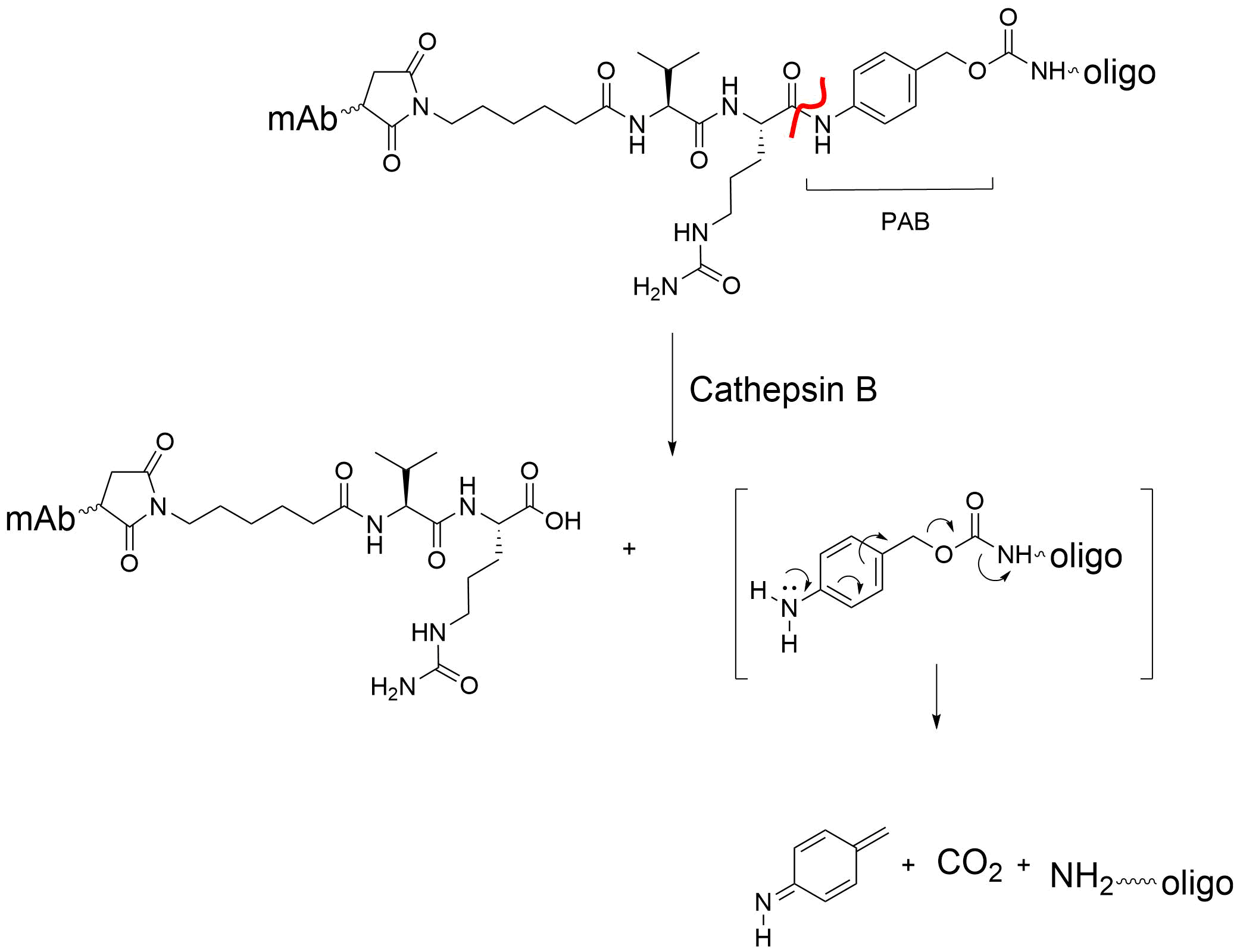

One of the features of this particular Val-Cit linker is the para-aminobenzyl (PAB) group. The PAB is a ‘self-immolating’ or ‘traceless’ linker which eliminates from the oligo or drug, the mechanism of which is shown in Fig. 6. The PAB is frequently incorporated into cleavable linkers to remove remnants of the linker after cleavage.

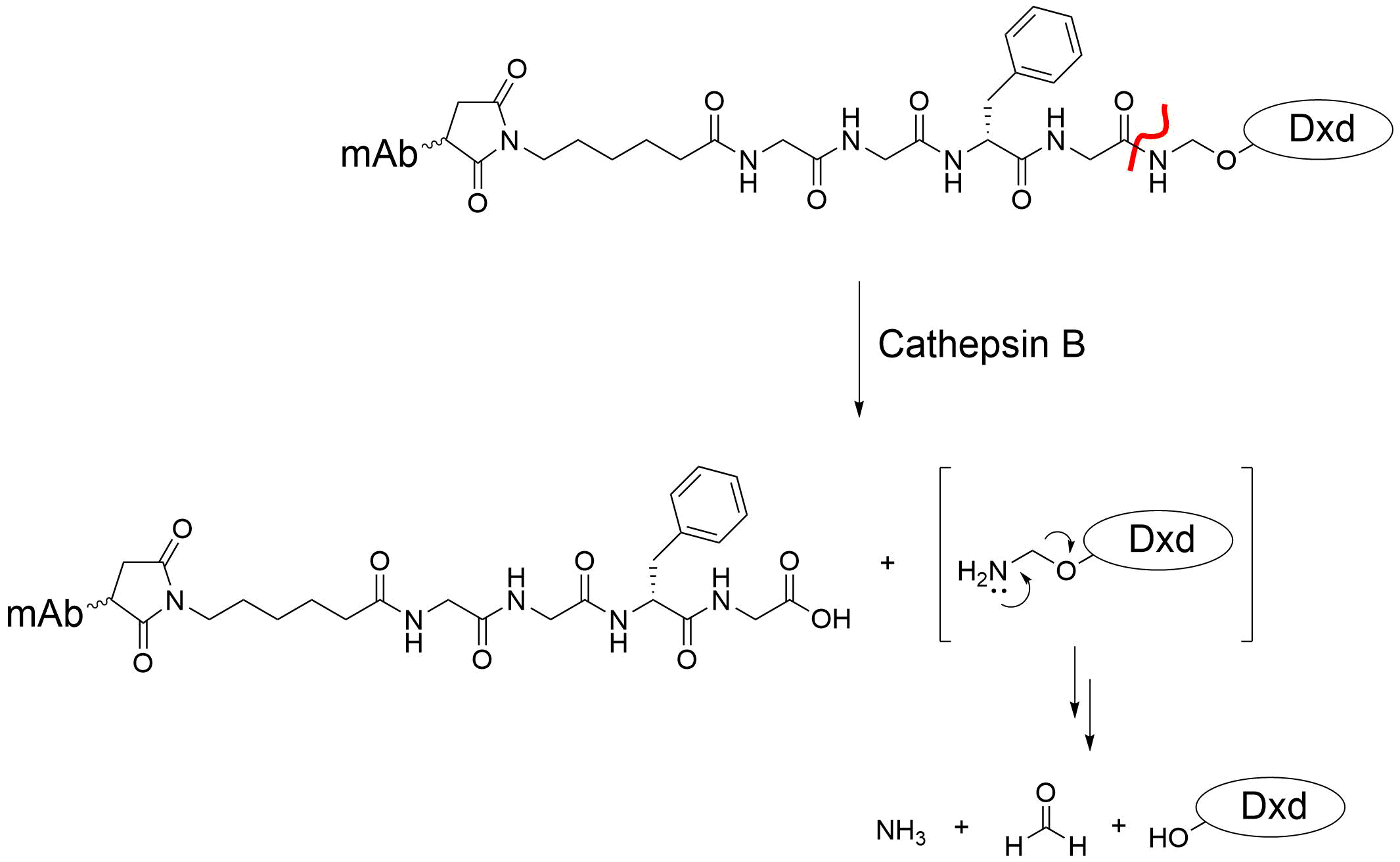

Another ‘traceless’ linker is an N,O-acetal. An example of this is the MC-Gly-Gly-Phe-Gly-AM linker that is incorporated into the ADC targeting HER2, Enhertu [1]. It too is cleaved by cathepsin B in a traceless manner, but without the use of the PAB (Fig. 7).

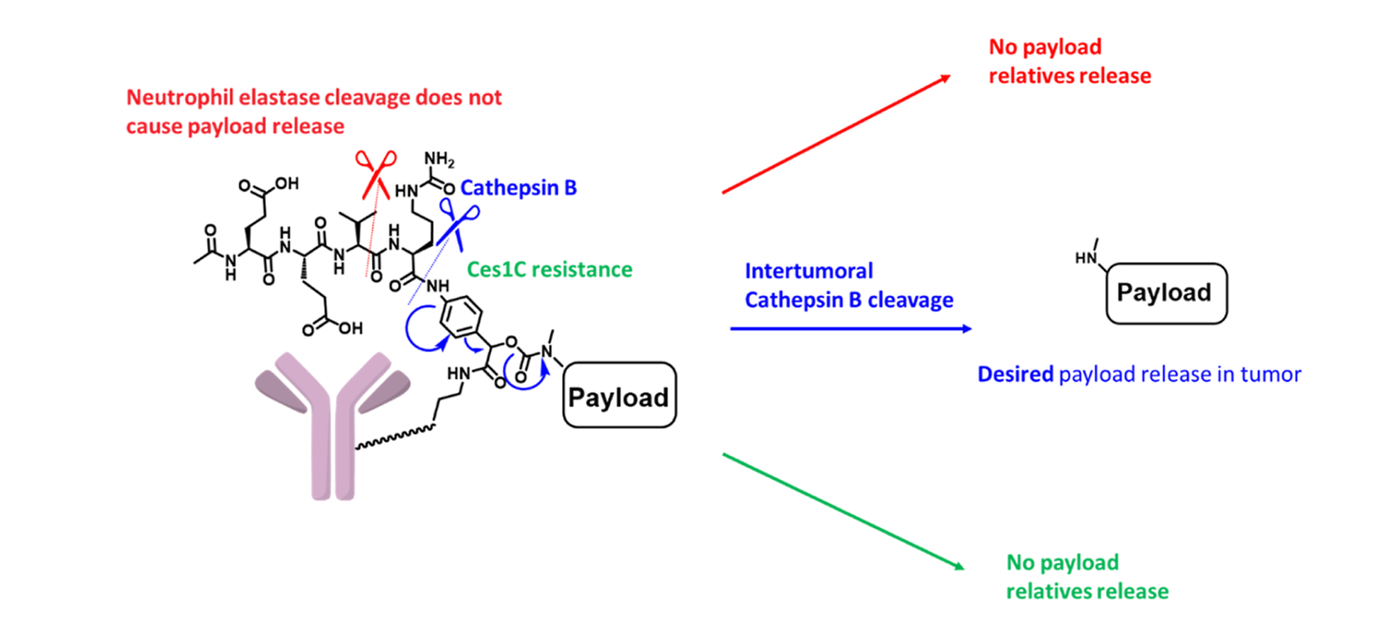

One complication of using the popular Val-Cit linker to develop new AOCs is that, unlike in human plasma, it’s cleaved in mouse and rat plasma by Carboxylesterase 1C (Ces1C) [5], which gives misleading results when using rodent models. A second issue with the Val-Cit linker is its susceptibility to Human Neutrophil Elastase (HNE) which may contribute to a patient developing neutropenia, as reported by Zhao[6]. To overcome these limitations, Matsuda designed a novel exo-linker that –

- Was susceptible to cleavage by cathepsin B

- Was resistant to payload release despite exposure to Human Neutrophil Elastase

- Was resistant to degradation by Ces1C allowing drugs to be developed using rodent models

The tripeptide of the exo-linker, shown in Fig. 8, is appended to the amino group of the PAB and does not act as a linker between the PAB and the mAb. Instead, the mAb is attached to the PAB itself. Because of this, while the Glu-Val-Cit tripeptide is a substrate for neutrophil elastase, the payload is not released even with cleavage. In the typical, linear tripeptide design, it would be. With the exo-linker, it’s only through the cleavage by cathepsin B that the PAB is activated, leading to payload release. Finally, the peptide used in Matsuda’s linker is a poor substrate for Ces1C, so rodent models can be used during development of new AOCs.

In conclusion, great strides have been made in designing cleavable linkers that are stable in plasma and are specifically released in the late-endosomes or lysosomes by enzymatic cleavage. The design of these linkers is critical to avoid unwanted cleavage by neutrophil elastase as well as for their use in rodent models during drug development. Linkers designed to cleave under low pH or reducing conditions found in the cytoplasm or endosomes, have been shown to have a relatively short half life in plasma before the payload is released. For this reason, linkers such as Val-Cit, and more refined peptide linkers, have grown in popularity but require careful designs and painstaking syntheses. This is contrasted with the simplicity of non-cleavable linkers that are quite stable under a variety of conditions and are simple and robust. Only time will tell which strategy will be considered the superior which surely will depend the type of therapeutic oligonucleotide used.

At Synoligo, we have successfully delivered on many complex oligo conjugation projects. Our extensive list of modifications and linkers gives you the flexibility and control you need to succeed. Let us know how we can help!

References:

[1] Linker Design for the Antibody Drug Conjugates: A Comprehensive Review, Lei et a., ChemMedChem, 2025 (20), e202500262; doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.202500262

[2] Structure−Activity Relationship of Antibody−Oligonucleotide Conjugates: Evaluating Bioconjugation Strategies for Antibody−siRNA Conjugates for Drug Development, Cochran, et al., J.Med.Chem. 2024, 67, 14852−14867

[3] Improving the Stability of Maleimide–Thiol Conjugation for Drug Targeting, Lahnsteiner, M.; Kastner, A.; Mayr, J.; Roller, A.; Keppler, B.K.; Kowol, C.R.. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15867

[4] Enzymatic glycan remodeling-metal free click (GlycoConnect™) provides homogenous antibody-drug conjugates with improved stability and therapeutic index without sequence engineering, Wijdeven MA et al., MAbs. 2022 (1) 2078466. doi:10.1080/19420862.2022.2078466

[5] Molecular Basis of Valine-Citrulline-PABC Linker Instability in Site-Specific ADCs and Its Mitigation by Linker Design, Dorywalski, et al., Mol. Cancer Ther. 2016 15(5):958-70.

[6] A Potential Mechanism for ADC-Induced Neutropenia: Role of Neutrophils in Their Own Demise, Zhao et al., Mol. Cancer Ther. (2017), 16 (9), 1866-1876.

[7] Exo-Cleavable Linkers: Enhanced Stability and Therapeutic Efficacy in Antibody–Drug Conjugates, Watanabe et al., J.Med.Chem. 2024, 67,18124−18138.