In 1977, the laboratories of Richard Roberts and Phillip Sharp independently discovered that the DNA sequences of genes were substantially longer than their respective mRNAs. This led to the discovery of introns and exons, the names coined by Walter Gilbert in 1978 for these ‘intragenic regions’ and ‘expressed regions’ respectively. Gilbert theorized that splicing allowed single nucleotide mutations to cause the addition or subtraction of entire exons from the protein, thereby speeding up evolution substantially by altering splicing patterns.[1]

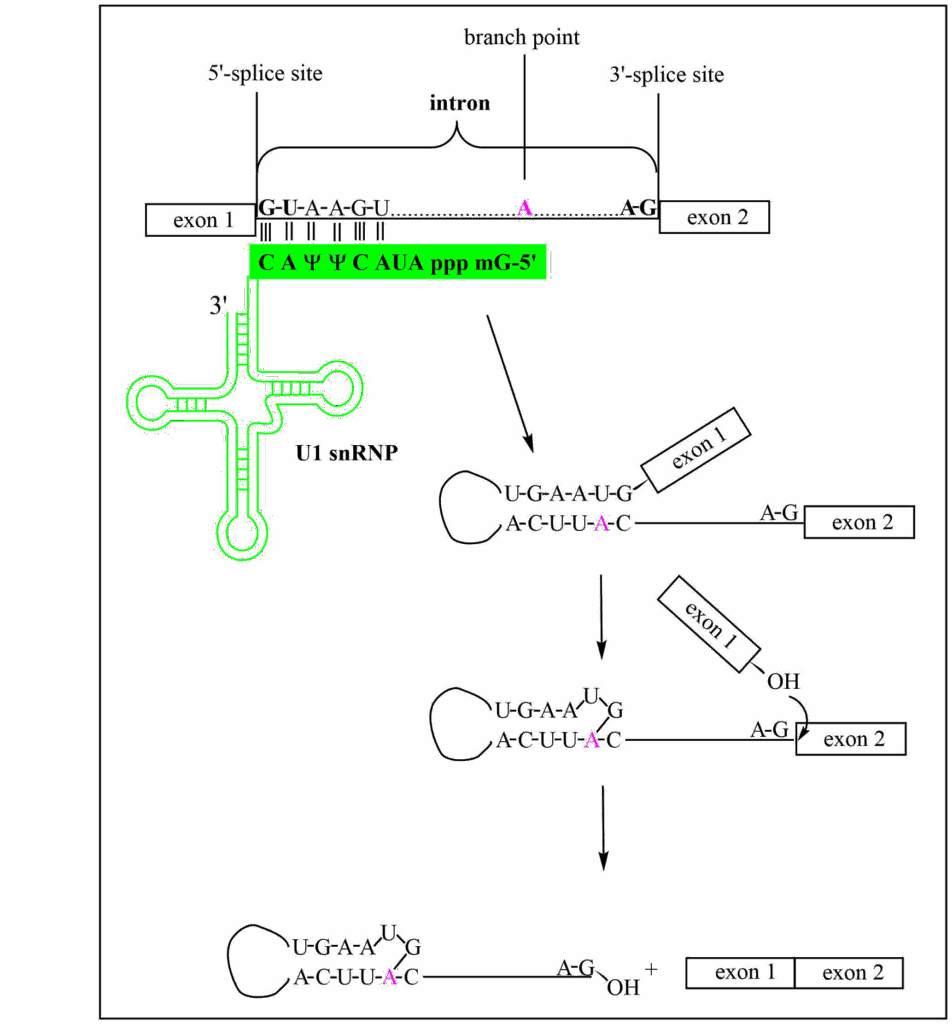

Splicing is carried out by the spliceosome which is composed of small nuclear RiboNucleotide Proteins (snRNPs) U1, U2, U4, U5, U6, and their associated Sm proteins. This forms a dynamic spliceosome structure with a molecular weight between 1.7 to 3.1 MDa as subunits are added and removed during the splicing process. Shown in Fig. 1 are the main pre-mRNA intermediates observed during splicing: recognition of the 5’ splice site by U1, folding the pre-mRNA into a stem-loop structure that brings the branchpoint adenosine vicinal to the conserved G of the 5’-splice site; the formation of lariat structure with a 2’-5’ linkage of the adenosine to the 5’-G of the intron causing the release of exon 1; and finally the nucleophilic attack by the 3’-OH of exon 1, leading to the cleavage of the lariat from exon 2 and the formation of the exon-exon junction.

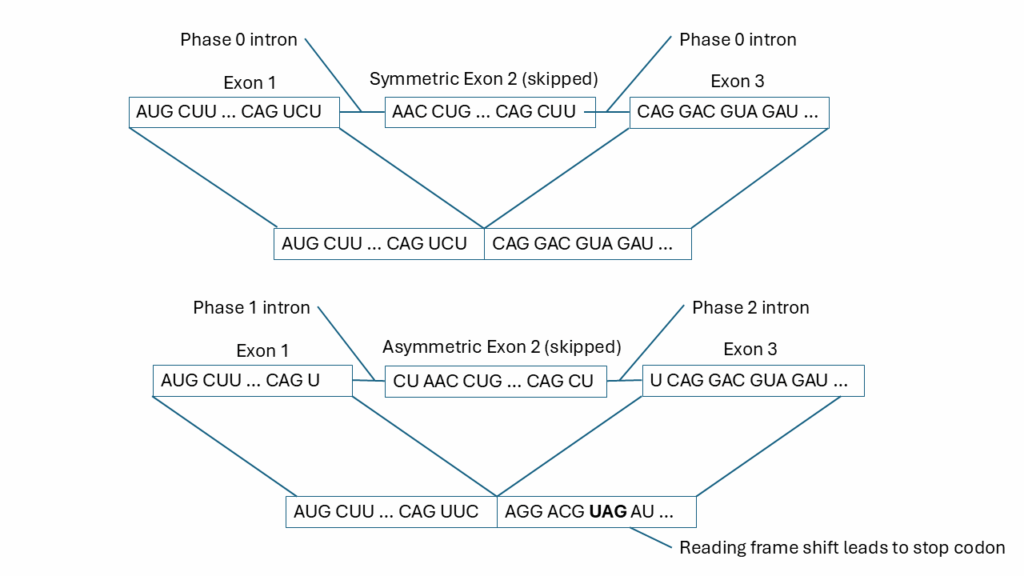

In Gilbert’s seminal 1978 Nature paper, he also proposed that there could be alternative splicing. Indeed, this proved to be the case. There are exonic and intronic splicing enhancers and silencers such that a single pre-mRNA can give rise to a variety of different mature mRNAs that are tissue-specific and/or development-specific.[2] There are three different types of introns – phase 0, 1 and 2. More often than not, introns are inserted between codons. These are phase 0 introns. However, introns can be inserted within an exon’s codon, either after the first base of the codon (phase 1 introns) or after the second base (phase 2). An exon is symmetric if its flanking introns are the same phase. In this case, if an exon is added or deleted, the proper reading frame for the protein is maintained. In almost all cases, exons that are alternatively spliced are symmetric. Asymmetric exons, on the other hand, have flanking introns of differing phases. If these asymmetric exons are deleted, then a frameshift mutation results in the mRNA and no functional protein is produced. Shown in Fig. 2 is a comparison of skipping a symmetric exon versus an asymmetric exon. When the symmetric exon is skipped, the reading frame is maintained in the downstream exon. However, when the asymmetric exon is skipped, the reading frame is disrupted, and a premature termination codon is introduced which triggers nonsense-mediated mRNA decay of the transcript. Most cases of Duchenne muscular dystrophy are due to the deletion of an asymmetric exon.

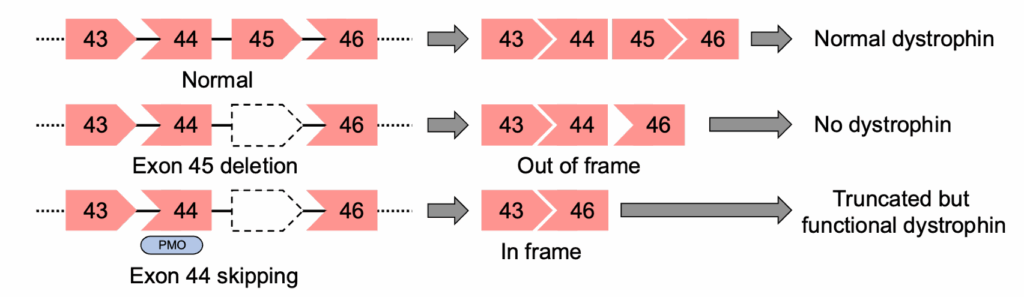

Dystrophin is the largest expressed gene in the human body and has 79 exons. The majority of Duchenne muscular dystrophy occurs due to exon deletions at two ‘hot spot’ regions where one or more exons are deleted: exons 2-20 and 45-55. Shown in Fig. 3 is an example of the deletion of exon 45 of the DMD gene. Exon 45 is asymmetric with its 5’ intron phase 0 and its 3’ intron phase 1 (shown as a pentagonal shape). Deletion of exon 45 leads to a shift in the reading frame and no functional dystrophin being produced. However, if an antisense oligo (ASO) blocks the splicing of exon 44, then the reading frame is restored, and a functional (albeit truncated) dystrophin is produced.

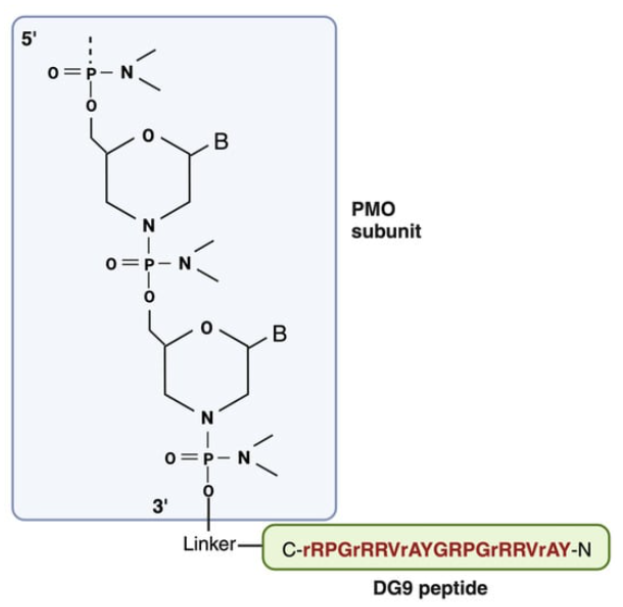

Arguably, the best choice ASO used to induce splice switching are phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs).

PMOs have two main advantages:

– Excellent stability in serum and essentially complete nuclease resistance

– Low toxicity and off-target effects

Splice-switching, unlike RNase H or siRNA activation, isn’t catalytic: the splice-switching oligo (SSO) must remain bound to pre-mRNA transcript until it has been processed or degraded. So, the SSO must be exceptionally stable within the cell to maintain activity and be at a relatively high concentration for highly expressed transcripts. With typical ASOs, to achieve the necessary stability requires a high number of PS linkages in the backbone, but this causes them to become increasingly hepato- and nephrotoxic, as well as lowering their affinity for the target sequences. For these reasons, PMOs are increasingly the preferred chemistry of choice for SSOs.

PMOs do have two disadvantages, however. Because they are charge-neutral, their solubility is relatively low, and it puts limits the oligomer length and G-content. The second disadvantage is that PMOs are poorly taken up in cells. For this reason, there has been a great deal of interest in cell-penetrating peptide-conjugated PMOs (PPMOs). Many of these cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) are positively charged and greatly increase PMO uptake and splicing efficiency, for example pip6a.[3] Unfortunately, in vivo, the pip6a-conjugated PPMO was plagued by the toxicity of the peptide itself.

A recently developed cell-penetrating peptide DG9 (Fig. 4) has been shown to have excellent properties. Not only did it greatly increase PMO uptake and exon skipping, it was essentially non-toxic.[4] This was attributed to the five D-arginine residues in the otherwise natural twenty-two L-amino acid peptide which reduced immunogenicity and toxicity. Using a humanized Duchenne muscular dystrophy mouse model (hDMDdel45;mdx), Shah et al. found the DG9-PMO increased dystrophin levels approximately 9-fold compared to the untreated controls, averaging over three tissue types, whereas the naked PMO was approximately half that amount. The biomarkers for liver damage, ALT and AST, were slightly elevated for the naked PMO; however, interestingly, the ALT and AST levels for the DG9-PMO-treated mice were statistically the same as wild-type. Likewise, the biomarker BUN levels that are indicative of kidney dysfunction were statistically the same as wild-type. Taken together, these data suggest DG9 to be an excellent CPP for PMOs. Other strategies to improve cell uptake are Fab/Antibody-PMO conjugates that target transferrin receptor 1, which is used, for example, in DYNE-251 that is now in phase 1 clinical trials.

When designing PMO sequences for slice-switching, it’s rather counterintuitive, but typically, the most potent antisense PMOs do not target the splice sites themselves but instead target the exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) sites. ESEs are short sequences found in the pre-mRNAs, typically 6 to 10 nucleotides in length, that SR proteins (Serine/Arginine-rich proteins) bind to and facilitate splicing. There are twelve SR proteins involved in pre-mRNA splicing for both constitutive exons (those exons which are present in all isoforms of a protein) and alternative exons (those which may, or may not be, spliced into the mature mRNA depending upon the cell state). They act either as enhancers or suppressors of splicing, among other functions.[5] When these ESE sites are blocked, the exon is skipped. An excellent resource to find accessible ESE sites within a sequence is ESEFinder. The ESEFinder program, which uses functional SELEX data to identify accessible SR protein binding sites, was developed in the Krainer lab.[6] Other programs identify regions within a pre-mRNA sequence that have a high probability of finding effective ESEs for focusing a ‘walk’ of antisense oligos to find the most potent exon-skipping PMO.[7] Often this walk is performed using less expensive 2’-OMe antisense oligos in vitro and then using PMOs for animal studies. Finally, we would be remiss if we did not mention the comprehensive paper by Aartsma-Rus et al., that describes in detail the guidelines for designing preclinical exon skipping antisense oligos.[8]

References

[1] Walter, G; Why Genes in Pieces?, Nature, 271(9), 501, (1978)

[2] Wang Y, et al. Mechanism of alternative splicing and its regulation. Biomed Rep. 3(2):152-158 (2015). doi: 10.3892/br.2014.407

[3] Gait MJ, et al., Cell-Penetrating Peptide Conjugates of Steric Blocking Oligonucleotides as Therapeutics for Neuromuscular Diseases from a Historical Perspective to Current Prospects of Treatment. Nucleic Acid Ther. 29(1):1-12 (2019). doi: 10.1089/nat.2018.0747

[4] Shah, M.N.A., Wilton-Clark, H., Haque, F. et al. DG9 boosts PMO nuclear uptake and exon skipping to restore dystrophic muscle and cardiac function. Nature Communications, 16, 4477 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-59494-8

[5] Slišković, I et al.; Exploring the multifunctionality of SR proteins. Biochem Soc Trans 50 (1): 187–198 (2022). doi: https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20210325

[6] Cartegni L, Wang J, Zhu Z, Zhang MQ, Krainer AR. ESEfinder: A web resource to identify exonic splicing enhancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 31(13):3568-71 (2003). doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg616

[7] Chiba, S., et al., eSkip-Finder: a machine learning-based web application and database to identify the optimal sequences of antisense oligonucleotides for exon skipping, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 49, 193–198 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab442

[8] Aartsma-Rus, A., Garanto, A., van Roon-Mom, W., McConnell, E. M., Suslovitch, V., Yan, W. X., … & N= 1 Collaborative. Consensus guidelines for the design and in vitro preclinical efficacy testing N-of-1 exon skipping antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acid Therapeutics, 33(1), 17-25 (2023).